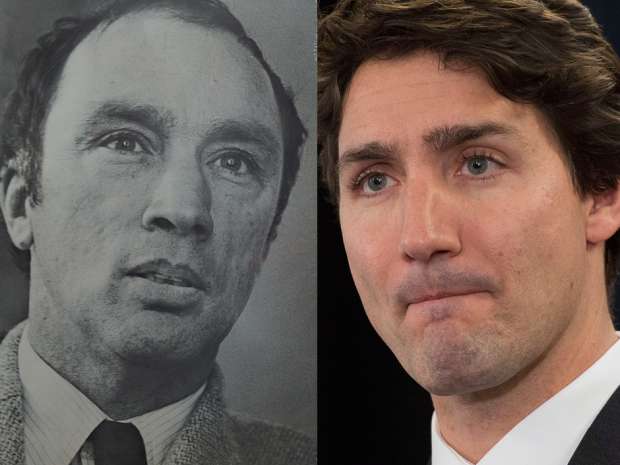

When I had been an undergraduate studying tax policy, I remember John Bulloch’s vicious attack on Pierre Elliott Trudeau’s tax reform package, which was particularly threatening to smaller businesses and investors. Bulloch, head of the Canadian Federation of Independent Business, was successful in paring back proposals that will have squeezed many Canadian entrepreneurs hard. As a result, the CFIB created a very large membership and became probably the most powerful advocacy groups in Ottawa.

Dan Kelly, the present head of the CFIB, includes a difficult challenge on his hand with Trudeau II, whose upcoming budget offers to curtail tax “loopholes” that encourage professionals and businesspeople to prevent personal income tax by creating small corporations. With proposed CPP expansion, the development of Ontario’s pension plan and municipal business-property-tax increases, Kelly and the membership face bad weather of cost increases brought on by tax-happy governments.

Actually, there is another whammy which has already hit small-business owners without sufficient comment: the Trudeau four-point hike in the top personal income tax rates. While Trudeau promises to deliver Harper’s proposed small-business corporate rate cut from 11 to nine per cent on up to $500,000 in profits, he’s already raised 2016 personal taxes on profits in excess of $200,000 derived by owners using their corporations.

Related

Jack Mintz: Putting a tiger in the Atlantic provinces’ tankJack Mintz: Bernie Sanders’ Canadian-style socialism

These personal tax hikes a lot more than swamp the benefits of the corporate tax cuts on new investments. As shown in the nearby table based on my recent use V. B. Venkatachalam, the effective tax rate on new investment rises one percentage point for Canada in general, with the largest increase in Alberta due to the Notley NDP’s simultaneous personal tax hikes. Smaller businesses are generally taxed more highly on their own investments in most provinces in 2016 except British Columbia and New Brunswick, which reduced their very own top personal tax rates (New Brunswick was reversing its ill-advised personal tax increase in the year before).

Kelly ought to be concerned as his membership has become taxed more heavily in 2016 than in 2015.

None of the is good news for economic growth. Start-ups generate many jobs and potential innovations that can have lasting effects around the economy. The recent mess-up in tax policy that sees higher federal marginal tax rates could be compounded by poorly thought-through policies like a proposed full taxation of stock options (which at least the Liberals now are reportedly wisely reconsidering).

In yesteryear I’ve been critical of some incentives that impede small-business growth, specially the excessively low small-business tax rate, especially at the provincial level. When a small business grows to become a large firm, it might be more heavily taxed. To prevent development in high-taxed profits beyond $500,000, many smaller businesses distribute income as highly taxed wages and salaries, interest or royalties to owners. Whatever strategy is used, growing smaller businesses are zapped by higher taxes if they succeed.

A smart government might have not increased the top personal tax rates, which stultify the incentive to take a position, work and take on risks. Instead, it would have cleaned up the tax system to reduce tax rates, complexity and distortions. Just one corporate income tax rate on large and small business could be hugely successful in increasing the tax system, allowing Canada to simplify its now highly complex dividend-tax-credit regime. This could tilt back the tax wall impeding small-business growth.

Now, this proposal would draw Dan Kelly’s ire, since it seems like another hit on small business. However, what would make more sense for smaller businesses are incentives that encourage their growth by flattening tax walls rather than making them more steep. Various research indicates that Canada’s economic growth has been hurt by policies that inhibit growth as firms have less incentive to develop.

Now, this proposal would draw Dan Kelly’s ire, since it seems like another hit on small business. However, what would make more sense for smaller businesses are incentives that encourage their growth by flattening tax walls rather than making them more steep. Various research indicates that Canada’s economic growth has been hurt by policies that inhibit growth as firms have less incentive to develop.

The U.K. features 100 percent tax depreciation for capital up to roughly $1 million in expenditure when it pushed its top corporate rate down to the little business rate. Expending capital benefits small businesses without hurting growth because the incentive is provided even if the small fish turns into a whale.

The U.S. provides a capital-gains tax cut to owners of small-business shares going public for the first time. This type of incentive clearly encourages growth rather than curtails it.

Some smarter ideas may be considered. One possibility is moving to some low, flat tax on dividends, capital gains and corporate income, as found in Scandinavia plus some other European countries.

The point is the fact that Canada needs to revamp its management of smaller businesses to create incentives to grow instead of stay small. Right now, the us government is on the wrong track; it needs to focus on what makes economies tick.

Jack M. Mintz is the President’s Fellow in the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy, and scholar-in-residence at Columbia School.

Now, this proposal would draw Dan Kelly’s ire, since it seems like another hit on small business. However, what would make more sense for smaller businesses are incentives that encourage their growth by flattening tax walls rather than making them more steep. Various research indicates that Canada’s economic growth has been hurt by policies that inhibit growth as firms have less incentive to develop.

Now, this proposal would draw Dan Kelly’s ire, since it seems like another hit on small business. However, what would make more sense for smaller businesses are incentives that encourage their growth by flattening tax walls rather than making them more steep. Various research indicates that Canada’s economic growth has been hurt by policies that inhibit growth as firms have less incentive to develop.